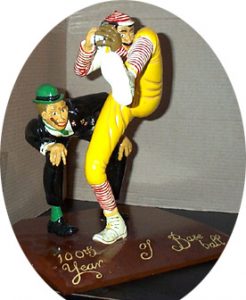

This unique piece is from the Phil Piton Collection and represents the 100th Anniversary of Baseball.

This unique piece is from the Phil Piton Collection and represents the 100th Anniversary of Baseball.

When Phil Piton took over Minor League Baseball as the fifth president of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, he was as well prepared to deal with the intricacies of the job as any man who’d ever had it.

Piton, who held the reins from 1964 until his retirement in 1971, had an intriguing resume. For 15 years, he had served as a top aide to Baseball commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis, where he became an authority on operations, rules and legal procedures within the professional baseball industry.

He left that post for a time during World War II, but soon returned to baseball when George Trautman was elected as the National Association president in 1947. One of Trautman’s first acts was to hire Piton as his assistant. Piton added to his reputation as a top administrator in the game during his 16 years in the job. When Trautman died in June, 1963, Piton was the logical choice to succeed him, and the membership voted him in at the Winter Meetings in San Diego that December.

Piton took over when Minor League Baseball was at a low ebb. The 1963 season ended with 18 leagues and 130 teams, the lowest totals (other than during the WWII shutdown) since the depths of the Depression. Total attendance had sagged to fewer than 10 million fans. It was a time when the industry’s biggest need was stability, and he was able to help provide it. When he retired following the 1971 season, Piton turned over 20 leagues and 155 teams to his successor, Henry (Hank) Peters. Attendance still was not booming, but the downward slide had ended and the upward progression had begun.

Phil was very promotion-minded and a strong backer of programs to make the ballpark experience more enjoyable for fans. He believed that much of the support for this needed to come from the central office, and he expanded a program of sending field representatives from the NA office all over the country to work with teams and share ideas.

Through his work in the commissioner’s office, and under Trautman in the NA office, Piton knew that it was vital for the Minor Leagues to work closely with Major League Baseball. Affiliations and support through the farm systems were the keys to survival.

As with his predecessors in the office of president, Piton had a war to contend with — this time in Vietnam. But it manifested itself in a different way. Instead of shutting down teams and leagues, it changed the way young manpower was available. Deferments from military service were available for college students, but only as long as they stayed in school. Major League Baseball teams encouraged their top prospects to stay in school and play baseball in the summer.

Minor League Baseball’s answer was to create short-season leagues that would not begin play until school was out and would end around Labor Day. Some of this was accomplished by converting existing full-season leagues to an abbreviated calendar, while some — the “complex” leagues — were new creations.

The complex leagues came into being in 1964 and 1965. They were beginning leagues for neophyte professionals, with games played at the Spring Training complexes of Major League teams, thus the designation for the group of leagues. In 1964, the Cocoa Rookie League and the Sarasota Rookie League began with four teams based at each of the Florida sites. A year later, the Florida Rookie League operated with six teams in Sarasota and Bradenton, eventually growing into the widespread Gulf Coast League of today.

With the need for additional sites for more advanced players, the Pioneer League switched to a summer-only schedule in 1964. The Northwest League followed suit in 1966, and the New York-Penn did the same in 1967. They joined the Appalachian League, which had been operating on that kind of a schedule since 1957. These Class A Short-Season leagues remain an important stop for many professionals in their earliest years.

Piton had to contend with a round of Major League expansion in 1969, losing significant West Coast markets in Seattle and San Diego. The other two expansion sites — Kansas City and Montreal — did not impact the NA, except that all four new teams would need new Minor League affiliates.

Late in his tenure, Piton had another war to fight. While Phil was a strong advocate of cooperation with the Major Leagues, he was not about to surrender the independence of the National Association. He was scheduled to retire after the 1970 season. That year also marked the end — temporarily — of Minor League Baseball in Columbus, Ohio — long the site of the NA office. The International League team was being relocated to Charleston, W.Va., and Piton knew there would a heavy push to move the office to a baseball city.

As it turned out, that push came from the top — a bid to move NA operations into the MLB commissioner’s office in New York City. Piton’s arguing logic prevailed. If it was so important for all of the offices to be under one roof, he reasoned, why had the National League office recently moved to San Francisco while the American League office remained in Boston? When Piton was persuaded to postpone his retirement for a year, the proposed move to New York was scrapped and the office remained in Columbus (until a subsequent move to its present location in St. Petersburg, Fla.)